Below you’ll find a piece written by one of my colleagues in the best tradition of bearing witness. Elizabeth Sell and her team have been visiting South Carolina, Florida and Tennessee to better understand poverty and hunger and how our work, especially summer meals sites, addresses it.

With so much attention these past two weeks on the presidential nominating conventions, Elizabeth’s reflections underscore the stakes for so many struggling children and families. If our political leaders saw from their podiums what we see on the ground and in the field, the national conversation would sound very different. The need for action on behalf of our children would take on greater urgency.

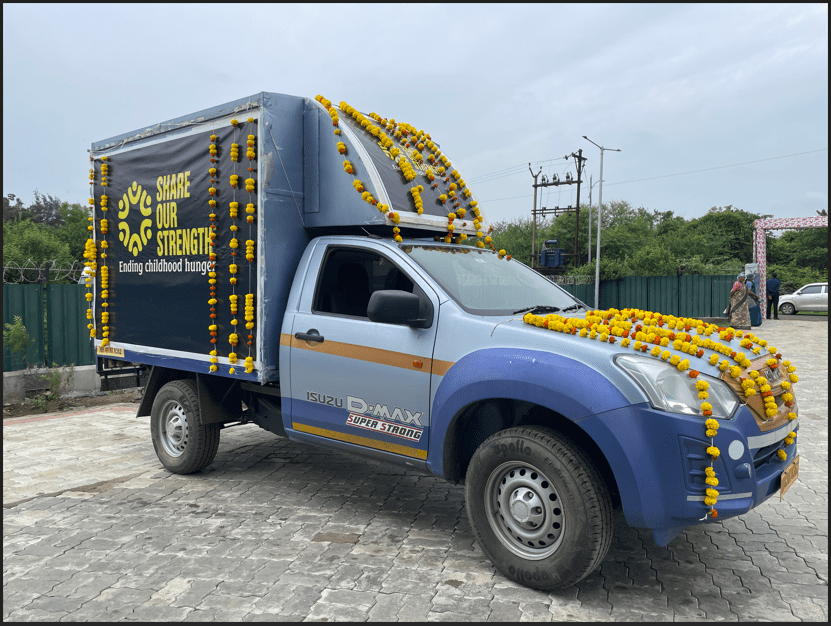

By the time the conventions are over we’ll have heard enough speeches to last a lifetime about why one candidate is better than the other. But we still won’t have seen or heard firsthand what the lives of Americans like Shaina, Sue, Patrick, and Scarlett, described below, are really like. At Share Our Strength, our No Kid Hungry campaign is committed to bringing you as close to those lives as possible through bearing witness.

Elections are vitally important because often only public policy can scale ideas that work and bring their benefits to all who need and deserve them. At its best public policy knits together the many strengths we each have to share, and makes America stronger as a result. Your vote in November is a way of bearing witness as well, to the nation American can and should be.

Elizabeth’s letter follows:

From: Sell, Elizabeth

Sent: Monday, July 25, 2016 10:55 AM

To: All Staff

Subject: Impressions From TN

Hi Everyone,

I wanted to share some impressions from my recent trip to our summer meals pilot project in Sneedville, TN.

If you find yourself in Sneedville, it’s because you live there, or you’re lost. Tucked in a valley in the Appalachian Mountains, reaching this small town in eastern Tennessee from any direction requires negotiating a series of hair pin turns up and down mountains. There’s no interstate nearby, the closest major town is about an hour away. Only about 6,000 people call this isolated community home.

I was in Sneedville because No Kid Hungry was conducting a summer meals pilot to test the best way to operate a “meals on wheels” style delivery model. We worked with our campaign partner in Tennessee, and a local church group to arrange a delivery system that drops off summer meals for kids either at their homes, or at drop-off points where families can pick-up the food and take it home. Shaina, an Americorps member and native of Sneedville was my guide. She patiently allowed me to tag along with a videographer, interviewing families as she dropped off food for their kids. Shaina’s four-hour route takes her all over this valley – up mountains, down dirt roads that are nearly impassable during heavy rains, and across some of the most beautiful, pristine country side you’ll ever see.

It was lucky I was with Shaina. Many families refused to let us film the food delivery, I can only speculate that they were both distrustful of outsiders and didn’t want to bring attention to themselves. There are still people in this community that don’t have indoor plumbing. Others lived in homes so dilapidated that front doors don’t shut properly, windows were missing glass, a well-placed boulder acts as a step up to the door instead of a deck or stairs. Many of these homes were surrounded by pieces of the family’s past, broken down cars and televisions, rusting farm equipment. Most of the area isn’t serviced by a trash pick-up, people have to bring their refuse to the local dump. It takes a car to get your trash to the dump, and money to buy gas for that car, so many people opt to let their trash build up outside in piles or in metal cans until there’s enough to burn.

Five days a week, Shaina loads up her SUV with a breakfast and a lunch for every child on her route. Faith and Natalia are one of her first stops. Faith is in her mid-twenties, but her life has already been destroyed by drugs. It was fitting that my last day in Sneedville was the same day Congress passed legislation to combat the opioid crisis in this country. Every single one of the families I met had been affected by the destructive forces of addiction. Faith’s first two kids were taken away by the state. Her daughter Natalia is just about a year old. Faith is pregnant again. She’s clean now, and living with two other women in a tiny, one-bedroom house at the end of a long dirt road. It’s tidy and orderly inside, but blankets cover the ripped plastic in the windows where the glass should be, you can’t help but wonder what will happen to them when it gets cold. Natalia is starting to eat solid foods and the apple sauce and cereals that come in the meal delivery help Faith save a bit her SNAP dollars. The women that live in the house all pool their food together to make it last a bit longer.

Sue never expected to be a mom for a second time. When her daughter’s life crumbled under the weight of addiction, it forever changed Sue’s life too. Her one-bedroom trailer isn’t meant for three people, but Sue and her two grandchildren make do. Patrick and Scarlett share a bed in the bedroom, Sue sleeps on a recliner. They live about 5 miles from the town’s only grocery store and don’t have a car. They’ve never been to a summer meals site because the kids have no way of getting there. People drive fast on the country roads, and Sue worries about people high on drugs hitting the kids if they walked or took bikes, but that’s a moot point since they don’t have bikes anyway. Sue skips meals sometimes to make sure the kids eat, when I ask her about it she just brushes it off. “I’m old, I don’t need much to eat anyhow.” Sue is always laughing, Scarlett and Patrick inherited that from her. And, they’re both honor roll students, clearly whip smart. Scarlett pulls me down to her level and then tells me that if I want to call her Charlotte I can, and then nearly falls over laughing at her own joke.

Chloe is delighted when we get to her house. She’s only five, but she loves people. We saw a snakeskin she found in the woods, we were introduced to all her dogs and cats. She insisted that I take her picture from many different angles. Louise is another grandmother that found herself entering a second round of motherhood. Her son struggles with addiction, he left Chloe and her baby brother Noah to be raised by Louise and her husband. Their cabin is nestled in a quiet meadow. It emerges like a bastion of comfortable, intentional solitude when you come upon it after a drive through the woods and up and down several steep mountain sides. Louise laughs when I ask if she’d bring Chloe to a summer meals site in the future, they only drive when it’s absolutely necessary. Gas costs money.

The program we’re piloting in Sneedville is doing exactly what it set out to do, it’s reaching kids in hard to reach places. This pilot has fed just a few of the children that rank among the millions missing out on summer meals programs because of the inefficiencies of the current program. If it doesn’t exist next year, those kids will continue to miss out. Transportation barriers are too immense to get them to summer meals programs.

The heartbreaking truth is that there are little kids just like Scarlett, Chloe and Patrick all over this nation, and they’re waiting for help. The way the current summer meals program is structured, however, we simply can’t reach them. That’s not good enough. It’s critical that we urge Congress to stand up for these kids. We need policies that let programs like the one in Sneedville become more than a pilot. We need policies that encourage innovation. But until Congress passes new summer meals legislation, help is not on the way for the millions of kids who struggle with summer hunger. Hungry kids can’t wait – join us in asking Congress to take action. Now.