I’ve been giving more thought to Bill Gate’s announcement, which I read about a few days after I returned from Haiti, of the largest philanthropic commitment in history: $10 billion over 10 years to develop and distribute vaccines for diseases like malaria, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. The burden of those infectious diseases on the poorest people in the world is every bit as crushing as the concrete rubble that buried so many in Port au Prince. Gates’ effort will catalyze a greater mobilization of talented medical professionals than anything we saw with Partners in Health. The lives of 8 million children will be saved by 2020 as a result. The $10 billion was a one day story.

The crisis in Haiti naturally trumped Gates as it did so much other news. For the media, nothing held a candle to the horrors being reported from Port au Prince, some so graphically that they became known as “disaster porn.”

Unlike in Haiti, the 3000 African kids who die every day from malaria die quietly and invisibly. That’s because they die routinely, year in and year out, in numbers too large to fathom. They die in the pages of medical journals, not in our living rooms on high definition TV. They don’t reach the threshold for Anderson Cooper. Or the 82nd Airborne. No rock concerts on MTV.

In reality there is nothing quiet about their deaths at all. They are painful, protracted, often horrendous. Perhaps worst of all, they are preventable.

This tension between the immediate and the long-term, between the personal and the abstract exists in every effort to create meaningful change. You and I have come up against it in virtually everything we do. It is human nature to be deeply moved by the drama in front of us, rather than what might be imagined for another time and place. You may have seen the Washington Post magazine story on new research that tries to explain it. Shankar Vedantam, a Washington Post reporter, wrote a book called “The Hidden Brain: How Our Unconscious Minds Elect Presidents, Control Markets, Wage Wars and Save Our Lives.” In it he says “The reason human beings seem to care so little about mass suffering and death is precisely because the suffering is happening on a mass scale. The brain is simply not very good at grasping the implications of mass suffering. Americans would be far more likely to step forward if only a few people were suffering or a single person were in pain…. Our hidden brain — my term for a host of unconscious mental processes that subtly biases our judgment, perceptions and actions — shapes our compassion into a telescope. We are best able to respond when we are focused on a single victim.”

Vedanta reviews the experiments of University of Oregon psychologist Paul SLovic who told volunteers given a certain amount of money, about a starving 7-year-old girl in Mali. On average, people gave half their money to help the girl. Slovic told another group of volunteers with the same amount of money about the problem of famine in Africa, and the millions of people in need. The volunteers gave half as much money as volunteers in the first group.

As with the model trains of our youth, only engines of a certain scale fit our mental tracks. They are very narrow gauge.

The consequence, while explainable as above, perhaps even understandable, is a spectacular failure of imagination. When we focus on the one rather than the many, on the symptom rather than cause, on what oneself can accomplish rather than on what needs to be accomplished by the broader community, we neglect our greatest opportunities to do the greatest good. It’s equivalent to suffering a massive stroke that leaves one seeing only what is in direct line of sight, with no peripheral vision or sense of relationship to the larger, surrounding world.

There is no recourse to such failure of imagination but to recognize it, confront it, and struggle to overcome it as one might a crippling stutter.

It would be nice if there were a more concrete and guaranteed prescription, perhaps a handy checklist to tick through like those Dr. Atul Gawande describes for hospitals, pilots and engineers. But overcoming failures of imagination has less to do with following procedure, or tapping external resources, and more with looking deeply and expansively within. It requires intentionally challenging one’s imagination, questioning whether we have engaged it to the fullest, and especially pushing to contemplate and react not only to what we see but also to what we don’t see.

A few years ago the commencement speaker at Wellesley College made exactly this point, telling the women in the class of 2006 about the ingredient essential to fighting for whatever may be their cause:

“Adam Hochschild writes beautifully about one such cause: the abolitionist movement, in his book, Bury the Chains. He states compellingly that ‘the abolitionists succeeded where others failed because they mastered one challenge that faces anyone who cares about social and economic justice: drawing connections between the near and the distant.’ Linking our own lives and fates with those we can’t see will, I believe, be the key to a decent and shared future….

“Imagination will allow you to make the link between the near of your lives with the distant others and will lead us to realize the plethora of connections between us and the rest of the world, between our lives and that of a Haitian peasant, between us and that of a homeless drug addict, between us and those living without access to clean water or vaccinations or education and this will surely lead to ways in which you can influence others and perhaps improve the world along the way.”

The commencement speaker was Ophelia Dahl. She explained how being the daughter of writer Roald Dahl meant learning a lot about imagination at an early age. She implied that it served her well in helping to envision and create Partners in Health. After all, PIH has succeeded where so many others have failed precisely because of a leap of imagination. The leap was not that highly educated docs in Boston would volunteer to provide health care to Haitians in Haiti – though it would be fair to call that a stretch in its own right – but rather that with the support of partners from Boston, Haitians could create and deliver their own health care. That is where imagination really triumphed.

The enormity of Gate’s $10 billion risks eclipsing the impressive feats of imagination that were its catalyst. Gates was able to see both sides of a distant coin: the needs of African children outside the small circumference of the telescope, and the transformative impact of vaccines notwithstanding a long roller-coaster history that has repeatedly dashed hopes and in the case of malaria for example has yet to produce a single licensed vaccine.

It’s the same imagination the cathedral builders had in persuading their community to invest fortunes and centuries in something that on paper had to look like the most improbable of visions.

It’s the imagination of Timberland’s Jeff Swartz who says a successful business can mean commerce and justice, the imagination that says childhood hunger can be eradicated, that says a malaria vaccine is not a matter of scientific discovery but biotech engineering.

Since returning from Haiti I’ve been determined, as many of us have, to try to make a difference there in the limited ways possible from here: tracking down needed supplies, working to find and connect resources, and engaging others to help. The trip did not fail to reignite and refuel commitment, as I knew it would.

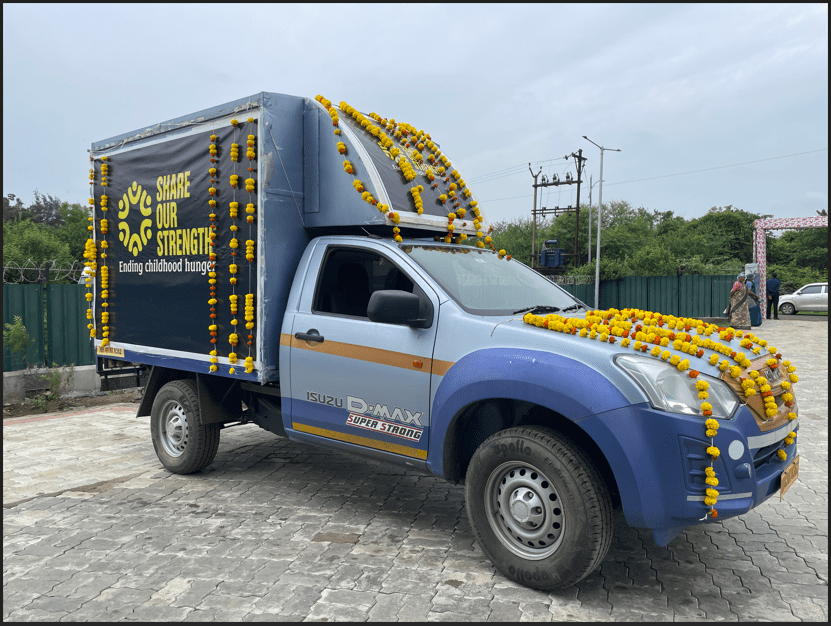

But ironically, for me at least, having witnessed the suffering in Haiti makes it more important to look beyond Haiti, not through it or past it, but beyond it, to find and fulfill one’s purpose. Anything less would feel like some tragic Greek myth in which we’d been warned that gazing too deeply into the eyes of Cite de Soleil’s children surging toward the back of the Yele food truck could permanently constrict our vision.

Compassion is both blessing and balm. But unless hitched to the power of imagination it can leave us one step behind the next tragedy, and the next, always a day late and dollar short. We’ll likely end up doing a lot of good, but not nearly good enough.

Moral imagination is supposed to be what differentiates us from the other species. But our boast is bigger than our bite. We remain only partially evolved, a work in progress to be admired and resisted both at once, or as Bruce Springsteen sings, we are “halfway to heaven and just a mile outta hell.”

If we hope to truly change the world rather than just the bits and pieces of it that drift in front of us, we must reach for more than the traditional tools stored in those drawers we glibly label “social entrepreneur”, “business leader” or “policy maker.” Indeed we must reach inside, not out, must shape our own evolution, with faith that the greatest value we can deliver may lie not in what we know but in what we seek to know.